Such seems to be the view of Justice Kagan in her dissenting opinion of the long-awaited ruling handed down by the Supreme Court on May 18, 2023 in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) v. Goldsmith et al.

The facts behind this case are as follows:

I. The facts

1981. Lynn Goldsmith is commissioned by Newsweek to do a photo shoot of a rising artist, Prince. The photos are used by Newsweek as part of an article devoted to the artist:

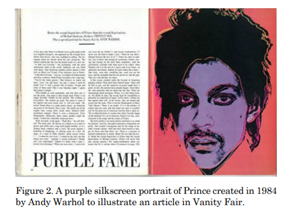

1984. In return for payment of USD 400, Goldsmith grants Vanity Fair a license to use one of the photographs as a reference to the artist for illustrative purposes, the license also specifying that the use was to be made only once. The license clearly includes the right for Vanity Fair to transform the photograph into an illustration. Vanity Fair commissioned Andy Warhol and publishes the illustration in its November 1984 issue:

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Andy Warhol at the same time silkscreens 15 additional portraits of Prince, which have not been published (“Prince Series”).

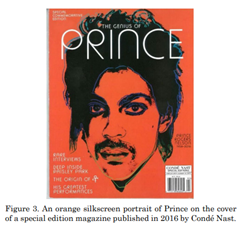

2016. AWF (Andy Warhol Foundation) grants Condé Nast a license to one of the images from this silkscreen for illustrative purposes, in return for a fee of USD 10,000. Goldsmith receives nothing.

On learning of this, Goldsmith informs AWF that, in her opinion, such use infringed her copyright. Litigation between AWF and Goldsmith ensues, taking the parties all the way to the Supreme Court.

What’s the problem?

II. The issue under copyright law

Copyright protects individual creations of the mind. While it is possible to use a copyrighted work to create another, the author of the original work must be asked for permission to create the derivative work on which it is based. This is what is known as a “derivative work”.

For example, a film based on a novel will be a derivative work of the novel, and will therefore require the writer’s agreement before it can be adapted for the screen. A derivative work thus uses a pre-existing work to transform it into something else, with the agreement of the original author.

All legal systems are familiar with this concept. This is the case not only in Swiss law (art. 3 al. 4 LDA), but also in American law, which is applicable here. Thus, § 106 (3) of the US Copyright Act provides that :

“Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do any authorize any of the following: to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work“

The original author’s right to agree and be paid for the re-use of his work, or to refuse to do so, is however limited by certain exceptions enshrined in the applicable law.

This is the case in Europe and Switzerland, for example, with the so-called parody exception, which allows anyone to parody a pre-existing work without needing to obtain the consent of the author of the work from which one is drawing inspiration, and risking refusal.

While the continental approach favors a clear and precise list of exceptions, American law has opted for a more flexible approach through the notion of “fair use“. Section 107 of the US Copyright Act reads as follows:

“Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include : (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

In this case, the question was whether AWF’s licensing of Prince’s illustration to Condé Nast infringed Goldsmith’s copyright in the underlying photograph, or whether it was a case of “fair use“.

While the SDNY had ruled in favor of AWF in the first instance, the Court of Appeal ruled that the conditions for the “fair use” exception had not been met, and that Goldsmith’s copyright had indeed been infringed. An appeal was lodged with the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case.

Why had the Court agreed to take up this case, and why was its outcome so closely scrutinized by intellectual property specialists?

III. The ruling

The main difficulty in this case was for the Court to interpret the first factor of § 107 to determine whether or not there was a case of “fair use”, in other words the “purpose and character of the use“.

Taking a slippery slope in this respect, American courts, including the Supreme Court, gradually interpreted this criterion by answering the following question: has the basic work been transformed by the work submitted for the court’s consideration? Assuming that this question was answered in the affirmative, it became common practice to accept the presence of a case of “fair use”, without examining the three other conditions laid down by § 107 of the US Copyright Act.

This development was denounced by many American authors, to the point that Professors Menell and Ginsburg filed an Amicus Curiae drawing the Supreme Court’s attention to the drift taken by American courts and the need to clarify the relationship between § 106 and § 107 of the US Copyright Act.

It should be remembered that derivative works, which are subject to the exclusive rights of their owners in order to be exploited, almost invariably require that the basic work be transformed. However, if the transformation of a work is sufficient to consider that there is a case of “fair use“, it is difficult to see what the difference is between a transformed work requiring the agreement of the owner of the work on which it is based, in application of § 106, and a case of “fair use” within the meaning of § 107, which does not require such agreement.

It was therefore urgent to clarify the situation.

Although the Amicus Curiae brief filed by Professors Menell and Ginsburg is never mentioned in the Supreme Court’s decision, I have little doubt that it left its mark and played a significant role in the outcome of this case.

In the Court’s view, Warhol’s transformation of Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince certainly adds certain features to the photograph, but in the end, it’s still a representation of the artist. All in all, Condé Nast’s use of Prince’s work does not differ greatly from the use the magazine could have made of Goldsmith’s photograph, and Warhol’s appropriation of Goldsmith’s work deprives Condé Nast of a market (that of press publishers) for which it could also license and be remunerated.

In reality, as interpreted under the first criterion of § 107, the transformation of the work must be much more profound. It must distort the purpose of the work taken over in order to give it a new one, hence the express reference in § 107 to the possibility of using a pre-existing work to comment on it, to use it for teaching purposes, for parody, etc.

This was not the case here, where both the photograph and Warhol’s illustration have a single purpose: to represent, albeit in different ways, an artist.

Accordingly, the Supreme Court ruled that the use of Goldsmith’s work in this case was not a case of “fair use”, but rather a derivative work that would have required his consent. To decide otherwise would be to gut § 106 of the US Copyright Act.

IV. Personal opinion

The judgment gives rise to a number of comments, the merits of which may of course be debated depending on one’s sensibilities:

1 In my opinion, the judgment is largely convincing. The Court has the merit of bringing a welcome clarification to the interplay of §§ 106 and 107 of the US Copyright Act, which had become particularly difficult to explain, with the risk of seeing the notion of derivative work emptied of its substance. This should not be the case, even if all the related questions and doubts have not yet been dispelled.

2. In my opinion, a few points remain regrettable:

Firstly, the fact that the Court expressly draws attention to the fact that its review is confined to the first criterion of § 107, i.e. the “purpose and character of the use“, to the exclusion of the other three which were not the subject of the appeal, leaves the door open to further discussion on the interaction of these different criteria.

Then there’s the fact that the Court clearly states that “[t]he Court limits its analysis to the specific use alleged to be infringing in this case – AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast – and expresses no opinion as to the creation, display or sale of the original Prince Series works“, a point that AWF made a point of noting on learning of the unfavorable judgment. In fact, since the case was brought against AWF and not Condé Nast, one wonders whether the real issue was not AWF’s transformation of Goldsmith’s photograph, rather than the mere use of this illustration in a magazine by Condé Nast, which was not a party to the proceedings.

In my opinion, it seems to me that it was very clearly the treatment of AWF that was at issue, as Condé Nast was not a party to the proceedings, and the Court should therefore have had the courage to qualify the nature of Warhol’s serigraphs in legal terms, a point that Judge Kagan does not fail to make in a footnote to her dissenting opinion:

“The statute – that is, the actual one – thus focuses attention on what the copier does with the underlying work. So when the statute more particularly asks (in factor 1) about the “purpose and character of the use” – meaning again, the “use made of [the copyrighted] work” – it is asking to what end, and with what result, the copier made use of the original“.

In this respect, Judge Kagan is, in my opinion, right, and the Court should have ruled on the silkscreen itself, and not on this single license granted to Condé Nast.

3. In reality, and Judge Kagan has clearly understood this, the difficulty lies in the drift shown by American jurisprudence, including that of the Supreme Court. In the case of Google LLC v. Oracle America, handed down on April 5, 2021, the Court ruled that the transformation of Oracle’s source code to interface with Google’s Android operating system was a “fair use” transformation.

However, as Judge Kagan points out, it is hard to see how Google’s adaptation of Oracle’s source code would have distorted the original work. If such a use amounts to “fair use”, one might well ask why it should be any different in the case of Warhol’s illustration of Goldsmith’s photograph.

In this respect, European law, with its interoperability exception, would undoubtedly have provided the Supreme Court with more promising avenues than a particularly perilous balancing act, leaving a number of questions open. While the Supreme Court’s Warhol ruling is an attempt to get back on track, its arguments in the Google case are hardly convincing, and still leave a number of questions unresolved – or at least not clearly resolved.

4. Notwithstanding these critical remarks, which are always easy to make a posteriori in a particularly complex case with multiple issues at stake, the Supreme Court reached a convincing result. Justice Kagan’s dissenting opinion is unconvincing, in at least two respects:

Firstly, because it sets itself up as an art expert, invoking the need to inspire one another and to protect Warhol because, after all, it is a Warhol. However, the Supreme Court is quick to point out that it is not there to assess the aesthetic character of a work, but to apply the law.

Secondly, and more importantly, at no point does Justice Kagan address the question of what would happen to the notion of derivative work if any transformation were to be considered “fair use”. The Court, on the other hand, responds to this central question by proposing what I consider to be a convincing way out, one that allows the two provisions to coexist.

5. There is little doubt that the ruling will be widely commented on and dissected. Its impact could be significant in certain areas, such as the rapid development of artificial intelligence. For example, it could – perhaps – mean that the reproduction of protected works for the purpose of training an artificial intelligence algorithm could, for the time being, be considered as a transformation denaturing the work from its original purpose and, consequently, satisfying the first criterion set out in § 107… Will this be enough to satisfy the other three criteria set out in this paragraph, and enable those who exploit training data sets to see this as a case of “fair use“? A case to follow, particularly in the context of the Midjourney and Stable Diffusion cases currently pending in the USA, where lawyers will certainly be keen to refer to this ruling.

6. Finally, it should be noted that in Swiss law, in what I believe to be a regrettable decision, the legislator has decided to protect photographs irrespective of their possible lack of individual character (art. 2 al. 3bis LDA). As of April 1er 2020, any reproduction of a photograph, however trivial, requires the author’s consent.

Notwithstanding the extensive protection afforded to photographers, it is accepted that the consent of the original owner of a protected work (not just photographers) is not required when the individual features of the original work disappear to make way for a work that can be considered “new” and totally independent of the original work; this is known as free use.

To take an example cited by Judge Kagan in her dissenting opinion, and regardless of the fact that Velazquez is now in the public domain, Francis Bacon’s extensive reworking of Velazquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X would fall within the scope of this free use, if only because, as mentioned above, the work is then distorted and its purpose altered, since we are no longer in the presence of a portrait as such:

The same could be said of Picasso’s reworking of the same Velazquez’s Meninas:

As for the Venus models, and again to address Judge Kagan’s objections to the depictions by Giorgione and Titian in particular below, perhaps we should first consider the individual, protectable character given to the arrangement and positioning of the figures, and whether this positioning and arrangement reflected a style specific to that period, which we know is not protected under copyright law. Assuming that that these features are deemed individual, and that we do not consider them to fade into the background in those of Titian, then in my opinion Titian’s work must indeed be considered a derivative work of Giorgione’s, which, in the light of our current legislation, would have enabled Giorgione to claim compensation for such exploitation:

Is such a result detrimental to innovation and culture? Should the notion of derivative works be reinterpreted and new limits set? If the question deserves to be asked, the answer must undoubtedly be provided by the legislator, not by a Tribunal which, as Montesquieu wrote in De l’esprit des lois, “[…] is the mouth that speaks the words of the law“. The Tribunal says the law; it does not write it. The Supreme Court has understood this, and we can only thank it for it.

Do you have questions about his topic?

Our lawyers benefit from their perfect understanding of Swiss and international business law. They are highly responsive and work hard to find the best legal and practical solution to their clients’ cases. They have acquired years in international experience in business law. They speak several foreign languages and have access to correspondents all over the world.

Avenue de Rumine 13

PO Box

CH – 1001 Lausanne

+41 21 711 71 00

info@wg-avocats.ch

©2024 Wilhelm Attorneys-at-Law Corp. Privacy Policy – Made by Mediago