On October 28, 2021, Mark Zuckerberg announced the change of Facebook’s name to Meta, underlining on this occasion in a keynote speech the efforts that the group intends to devote to the Metaverse.

Whether you love or hate Zuckerberg, his interest in the Metaverse means that you can’t dismiss this phenomenon out of hand.

What is it about? In short, the Metaverse aims to allow the user not to look through the screen, but to live the experience as if he was in the screen, within a three-dimensional universe of which he is an integral part thanks to accessories that extend his senses into a digital universe, making him, in a way, a digital self, such as haptic gloves, helmets and other virtual glasses.

If the gaming world is undoubtedly one of the first we think of in this respect – proof of this is the valuation of Roblox at USD 41 billion after its IPO, a real public plebiscite in favor of the Metaverse – the phenomenon can, potentially, affect any field, whether it is social relationships, the broader entertainment industry, sports, work and, also and perhaps especially in the mind of Zuckerberg, commerce.

We have to admit that the technology seems to be ready for this, whether we think of 5G making the advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) ever more possible, the probable advent of quantum computing in the years to come, or even the one that is about to happen, the Internet of Values dear to Tapscott, made possible by the use of blockchain technology and its derivatives such as NFTs (Non Fungible Tokens).

The legal issues related to the Metaverse promise to be numerous and to keep lawyers busy in the years to come. Without claiming to be exhaustive, let us mention a few of them:

Like the early days of the Internet, the emergence of the Metaverse has sparked the interest of libertarians. In an era where decentralization is the order of the day thanks to technologies such as blockchain, many like to believe that community governance through DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) and the rise of digital commerce based on NFTs will emerge, making the need for centralized institutions and intermediaries like banks obsolete. Some worlds like Decentraland or Sandbox would be possible examples.

Nothing is impossible. However, we cannot ignore the fact that the main players interested in this market to date are multinationals like Microsoft, Google or Meta (formerly Facebook). It is hard to believe that these players do not see in the Metaverse the possibility to substitute advertising revenue models – which are certainly flourishing but will reach their limits sooner or later – with real commercial transactions between users in their digital worlds, thanks to crypto-currencies as Facebook tried to do in our real world with the failed introduction of LIBRA. In doing so, these companies could continue to achieve their growth objectives to the delight of their shareholders…and executives.

Imagine a parallel universe where you buy digital land, build a digital house, buy a digital car and then engage in various digital purchases on a daily basis to live your digital life, all financed by crypto-currencies. Without wanting to paint the devil on the wall, we can think that this vision is not far from Zuckerberg’s…

In this scenario, we would then be far from libertarian universes, at least in the sense that users understand it, but rather universes controlled by the members of FAANG with an absence of awareness on the part of state actors. The libertarian universe would then be the one that these multinationals wanted, controlled by these actors.

In view of these risks, it is in the interest of governments to quickly take an interest in these issues, understand them and deal with them.

One of the challenges, and not the least, will be to know what law is applicable to these parallel universes. From the moment when individuals from the most diverse horizons are able to find themselves within the same universe, universes which, moreover, may be connected to one another, it is easy to imagine the difficulty that there may be in deciding on the law applicable to relations between individuals.

One thing seems certain: these universes will be subject to general conditions that can be expected to form an increasingly important privatization framework that will largely replace the state legal framework. This ever-increasing privatization will undoubtedly require an even stronger approach to the governance of these universes, a governance that is becoming ever stronger as evidenced by the RGPD or the proposed regulation on artificial intelligence. No doubt the Metaverse will not escape this either.

Could we go further and consider that these parallel universes be subject to their own rules and jurisdictions, for example autonomous digital arbitration tribunals applying a kind of lex mercatoria specific to the Metaverse and detached from any legal order?

The advent of the Metaverse will also be about metadata. For the Metaverse players, who have so far been largely centered in the United States, resolving the issues of data transfers with Europe, which have become so complicated since the Schrems II ruling, is a priority; witness Zuckerberg’s recent threat to shut down Facebook and Instagram in Europe if European users’ data cannot be uploaded to servers located in the United States.

As for users, they cannot ignore the fact that, from personality profiles made possible today by the massive collection of online data, we will move to real emotional profiles, thanks to the metadata collected by the devices interconnected to these universes (helmets, gloves, various sensory detectors).

Those who control these universes will then be able to read the minds of users in an open book, with all the manipulations that one can imagine, in an interest that, one can fear, will not be that of the users.

Data protection, which is already important, will then become a crucial democratic issue so that the prospect fantasized by some of a libertarian universe does not turn into an Orwellian universe.

Imagine a world where you no longer consume only in the real world, but every day in the parallel universes where you live your digital life, where you buy your digital goods, your digital home, your paintings and other artistic works in the form of NFT, all paid for with crypto-currencies.

The advent of the Metaverse could also be the advent of the massive democratization of crypto-currencies, leaving FIAT currencies and the control exercised by the authorities on the matter on the sidelines. If Switzerland is a pioneer in the regulatory framework that now governs the issuance of tokens, it is likely that it will not carry much weight in a largely decentralized global universe where the joint efforts of institutions and private players such as banks will certainly be necessary to prevent private players from taking control in this area.

One can easily imagine the importance of intellectual property rights in these worlds, starting with copyrights.

Let’s bet that the Metaverse will be the era of all kinds of licenses, with a possible essential role played by NFTs and the right of access conferred to the works they incorporate, acquired through crypto-currencies. The questions of ownership of rights and the extent of the licenses granted will then take on an essential role in this universe.

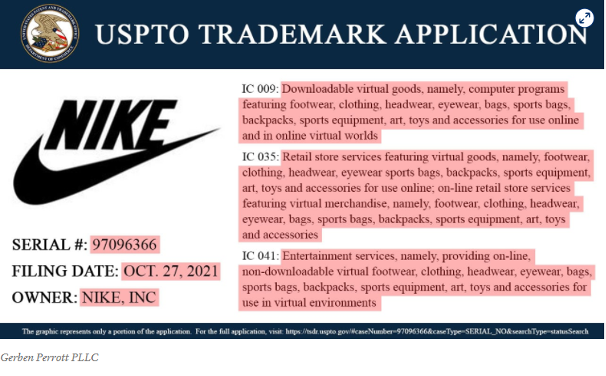

Brands will not be left out. Many players have already understood the interest that their presence in the Metaverse could present for them, by proposing virtual products offered under their brand. However, it is difficult to predict at this point whether a registration for products, so far thought of as tangible goods, will also cover such products in digital form, or whether a dedicated registration will not be necessary. Should the sale of a shoe be considered equivalent to the sale of a digital shoe? Some, such as Hermès, have not hesitated to file suit in the United States District Court Southern District of New York against what they consider to be an infringement of their trademark against the sale of digital goods in NFT form. Others, such as Nike, prefer to cut the debate short and have already started to adapt their registrations, making sure to protect their trademarks also for digital goods, more specifically in classes 9, 35 and 41, classes that could take a particular boost with the Metaverse.

Finally, from a patent perspective, the success of these universes could largely depend on their interconnectivity and, consequently, on the adoption of standards. In this context, Standards Essential Patents (SEP), which are already crucial in the field of telecommunications and IoT, could play an increasingly important role, perhaps making governance more systematic than it is today wishful.

If we cannot ignore the numerous advantages that the Metaverse could present in certain aspects such as the world of work, education or, at least from certain angles, social relationships, we cannot help but feel a certain anguish when faced with the digitalization of the individual that it induces.

Far from a libertarian world as some people fantasize, the Metaverse could on the contrary turn out to be a universe even more controlled by members of FAANG, eager to replicate a digital universe where consumerism would be omnipresent on an almost infinite scale, with a decentralization made possible by technologies like blockchain without any state control whatsoever, or at least very tenuous.

Apart from the legal aspects, we cannot ignore the social fears raised by the Metaverse. Will we see over time a rapprochement of the real world with these parallel universes to the point, for certain fragile people, of taking refuge in them as Mallorie does in Inception (Christopher Nolan), or of fleeing from one’s own emotions in order to connect to an empathy box as Rick Deckard does in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (Philip K. Dick) ? At least today reality seems to be able to come closer to these dystopias. Is there any reason to be happy about this? To each his own opinion. For my part, I hope that my children will continue, notwithstanding the possible existence of parallel universes, to make their own the words of Clarisse in Fahrenheit 451 (Ray Bradbury), another dystopia : ” I like to feel things, to look at things and sometimes I spend all night standing, walking, and I watch the sun rise “.

Do you have questions about his topic?

Our lawyers benefit from their perfect understanding of Swiss and international business law. They are highly responsive and work hard to find the best legal and practical solution to their clients’ cases. They have acquired years in international experience in business law. They speak several foreign languages and have access to correspondents all over the world.

Avenue de Rumine 13

PO Box

CH – 1001 Lausanne

+41 21 711 71 00

info@wg-avocats.ch

©2024 Wilhelm Attorneys-at-Law Corp. Privacy Policy – Made by Mediago